#224 Wright Flyer III

1905

The first practical airplane

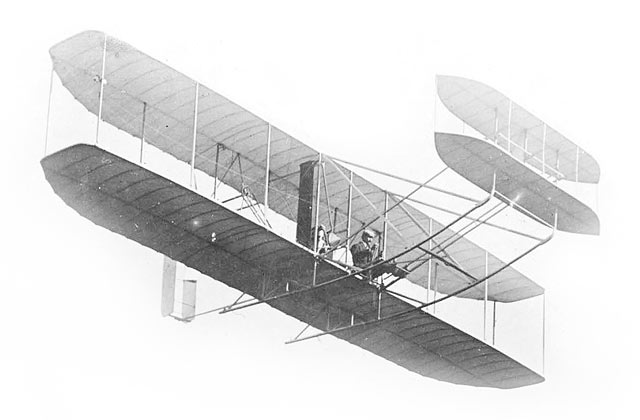

The 1905 Wright Flyer III, built by Wilbur (1867-1912) and Orville (1871-1948) Wright, was the world's first airplane capable of sustained, maneuverable flight. Similar in design to their celebrated first airplane, this machine featured a stronger structure, a larger engine turning new "bent-end" propellers, and greater control-surface area for improved safety and maneuverability.

The Wrights made several modifications to this flyer and learned how to perform aerial maneuvers safely during a series of flights at Huffman Prairie during 1905. The plane was dismantled after these flights, but rebuilt and flown in 1908 at Kitty Hawk, and ultimately restored for display in 1950 for Carillon Historical Park.

The first powered flight by Orville Wright on December 17, 1903, lasted 12-seconds and covered 120 feet, marking the first time a human had successfully piloted a self-propelled machine that rose into the air on its own power and landed on ground as high as that from which it had taken off. The Wright Flyer had indeed flown, but basically in a straight line and only a few feet above the ground. To be truly practical, an airplane would have to be able to climb to an altitude that would clear trees and buildings, and it would need to be fully maneuverable. In addition, a practical airplane would have to be reasonably safe and easy to control.

The Wrights began work on Wright Flyer III on May 23, 1905. Like their two previous airplanes, Wright Flyer III was a biplane with a dual canard elevator, dual pusher propellers, and a dual vertical tail. The tail was taller, and the entire craft sat slightly higher off the ground, but it was much like Wright Flyer II, which was flown during 1904 and early 1905. In fact, the engine and almost all of the metal hardware from Wright Flyer II was reused in the all-new airframe. In the new plane, the brothers returned to their 1903 wing camber of 1/20 of the wing chord. As with the 1903 engine, the 1904-05 engine was designed by the Wrights and built by Charlie Taylor.

After several attempts, the brothers rebuilt Wright Flyer III improving the elevator and getting pitch under the pilot's control. They increased the elevator surface area by over 50 percent and, more importantly, moved the whole elevator assembly almost 5½ feet farther in front of the wing. This moved the center of mass farther forward and lengthened the moment arm through which the elevator acted. The relocated center of mass made the craft less likely to pitch upward, and the increased length made the plane less sensitive to minor elevator movements, thus reducing the likelihood that a pilot would over-correct for a perturbation in pitch.

In addition, the Wrights decided to give the pilot independent control over the axes-pitch, roll and yaw. Heretofore the rudder had been connected to the wing-warping control and both moved together whenever the pilot moved the hip cradle. They added a second control handle-the first one moved only the elevator-so the pilot could pivot the rudder independently. To reduce the nose dropping in turns they added two vertical, semicircular vanes they called "blinkers" between the two elevators.

These changes took some getting used to in flight, but the Wrights realized a vast improvement in performance from the first flight of the rebuilt Wright Flyer III on August 24, 1905. Within a week, Orville had completed four circuits of the field, remained aloft for almost five minutes, and landed back where he started without crashing. Most importantly, they finally had decent control over pitch and the dangerous oscillations. Soft, controlled landings became the norm, as did increasingly longer flights.

Once again, on October 5, 1905, Wilbur flew until his fuel was exhausted, only this time he had enough to remain aloft for 39 minutes, 24 seconds, covering slightly over 24 miles, a distance longer than all of the previous 109 flights put together. Unlike anything else in the world, it could take off, climb into the air, fly for extended periods in any direction completely under the pilot's control and land in a safe, controlled manner. And it had shown that it could do all of this over and over again. While some fundamental changes in airplane design would come in the future, the primary one being the relocation of the elevator to the tail of most planes, the basic concepts proven by the Wrights with Wright Flyer III remained the foundation for these designs.

Except for the 1903 Wright Flyer, the Wrights did not consider their flying machines particularly historic or worthy of preservation. (The first Wright Flyer of 1903 is displayed at the Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.) In 1947, Edward Deeds, then chair of Dayton's The National Cash Register Company, envisioned a park to celebrate the Dayton area's contributions to industry and transportation. Deeds asked for Orville's help in selecting a machine for display. Wright eventually recommended that Wright Flyer III be rebuilt for the exhibit and in spring 1947 oversaw every detail for authenticity. Eighty percent of all but the fabric was original, but some new parts had to be made to replace missing or destroyed originals. The 1905 engine was reinstalled, though with a new crankshaft and flywheel, parts that had been taken to restore the 1903 engine some years earlier. The restoration took more than a year and Orville Wright died January 30, 1948, before the completion of the aviation hall. The restoration was unveiled to the public at a grand ceremony on June 3, 1950. Since then, Wright Flyer III remains one of the most significant artifacts in aviation history.

In 1990, the 1905 Wright Flyer III was designated a National Historic Landmark, the first airplane in the United States to receive such a designation. Housed in John W. Berry Sr. Wright Brothers Aviation Center (a complex of four connected buildings-the replica Wright Cycle Company, Wilbur Wright Wing, Wright Hall and Orville Wright Wing), it is owned by the private nonprofit Carillon Park. It is one of four sites in a unique public-private partnership park, the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park.

In 2000, in preparation for the centennial of powered flight celebration and with the assistance of a Save America's Treasure's grant, the Wright Flyer III was completely restored for the first time since Orville Wright restored the plane for exhibition.

Visiting Info

Dayton History at Carillon Park

1000 Carillon Boulevard

Dayton, OH 45409

Self tours are available in the summer months;

April to October guided tours take place daily.

Hours: Monday - Saturday, 9:30 AM - 5 PM; Sundays 12 - 5 PM.

For further info visit Dayton History at Carillon Park or call 937-293-2841.

Directions

Take I-75 to Edwin C. Moses Boulevard (Exit 51). Left onto Edwin C. Moses, then right on Stewart Street. Right on Patterson Boulevard and right on Carillon Boulevard. Park entrance is on the left.

Useful Links

Carillon Historical Park www.daytonhistory.org

Ceremony Notes

February 20, 2003. ASME President Susan H. Skemp presented the bronze landmark plaque to W. Anthony Huffman, chair of the Carillon Historical Park Board.

Plaque location

John W. Berry Sr. Wright Brothers Aviation Center (within the Park)